|

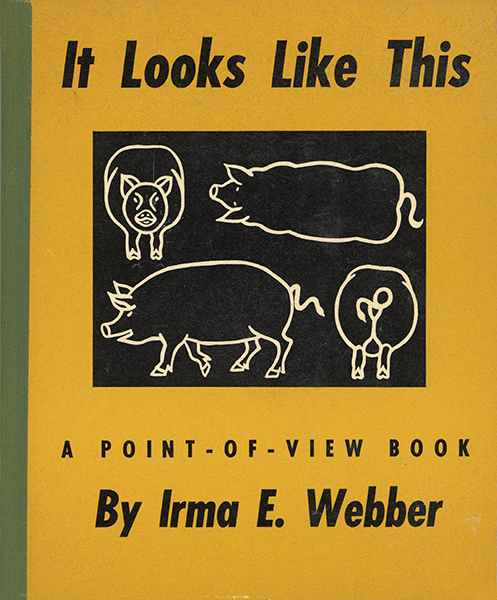

article in The Horn Book

Magazine, Sept.-Oct. 1947

R. S. V. P.

By IRMA E. WEBBER

With drawings by the

author

SOME

invitations are precisely worded, beautifully

engraved, and even gilt embossed. They

generally come in two envelopes. Less elegant

invitations, to perhaps more pleasurable

affairs, are sometimes painstakingly penned or

hastily scrawled. Others are casually extended

over the phone or over the fence. Still others

come to us in such camouflaged form we may not

heed them because we do not readily recognize

them.

Some of my most

memorable invitations have been worded simply,

"Mommy, come see! " They were first extended to

me when my husband, son Herbert, and I were

living at the foot of Riverside's Mt. Rubidoux.

In those days, I frequently whizzed through the

housework in order to study the anatomy of

plants while Herbert played. My converted

breakfast-nook laboratory overlooked the large,

completely fenced back-yard playground, so I

could alternate studious gazing into the

microscope with motherly glancing out the

window. While this arrangement permitted some

botanical progress, the periods of study were

frequently shortened by Herbert's eager

invitation, "Mommy, come see!" In the years

since, I've been thankful that I sensed this was

an invitation, rather than a mere interruption,

and that I so often went to see what Herbert

wanted me to see.

What was I invited

to see? Nothing the newspapers considered

newsworthy. Nothing my adult friends picked as

topics for conversation. Just matters of genuine

interest to a small boy: little, crooked plants

that pushed up the soil; taller, straighter

plants that pread out new leaves; the

California Poppy bud that doffed its dunce cap;

the tomato that was red enough to pick; the

honey bees that buzzed about the rambler roses;

the birds that pecked the figs; the glistening

trail left by a snail; the lizard that climbed

the pergola; the water that gurgled out of a

gopher hole; the ants that labored with their

loads; the worms that wiggled in the mud; the

clouds that floated in the sky; the shadows that

changed. shape. These are but a few of the

things I was invited to see in Herbert's

backyard world.

I soon learned that,

so far as Herbert was concerned, " Mommy, come

se!" didn't always mean " see " in the visual

sense. Often the invitation was really to touch,

or smell, or listen. Herbert soon discovered

that different parts of a rose bush don't all

feel and smell alike, and that there is no more

similarity in the feel of stickery rose leaves

and sticky petunia leaves than there is in the

fragrance of roses and petunias, or the song of

jays and canaries, or the flavor of carrots and

spinach. As Herbert, without assistance,

repeatedly discovered significant similarities

and differences in the things about hin;i, I was

repeatedly struck with the contrast between the

sharp observations of a young child anxious to

learn, and some of the perfunctory, slipshod

observations I had encountered among college

students who admittedly enrolled in science

courses solely because some science was required

for graduation.

When Herbert was

nearly four, Irma Jean was born. By the time she

was two, she also invited me to "see" many

things. Her interests in backyard matters were

as varied, and her observations as keen as

Herbert's had been in his pre-school years.

Moreover, they clearly indicated a lack of any

inborn, feminine dislike of mice, grubs,

spiders, or mud.

When Irma Jean was

not quite three, I enrolled her in a small, but

very good, nursery school. She was delighted

with the idea of going to school as Herbert did,

and she thoroughly enjoyed the school

activities. With both children in school five

mornings a week, I once again found a good deal

of time for intensive work on plant anatomy. The

whole family was very happy until the nursery

school director moved away and the nursery

school closed. This meant, that after having

experienced the companionship of children her

age and the assorted activities of school, Irma

Jean couldn't go to school because she had

suddenly grown too young. It also meant that I

had a broken-hearted youngster who knew she was

old enough for school because she had gone to

school for about a year. I couldn't stand seeing

her so forlorn, and felt that the least I could

do to attempt to cheer the child was to supply

some of the school activities that she craved.

Accordingly, for the next year, a large share of

my time and energy was devoted to running a

sort of one-child school.

Fortunately, the

back-yard still invited a great many

observations and activities. The near-by rocky

slopes of Mt. Rubidoux invited hikes midst

chaparral and its dwellers. The house invited

mastery of simple tasks. Clay, blackboard and

chalk, paints, crayons and paper invited

artistic expression. And fortunately, the

junior branch of the public library invited even

those who were "too young" for school.

Our junior branch

library doesn't extend its invitation in the

most modern or elegant housing in town. No, its

invitation is just an unpretentious, genuine

welcome to all, betokened by good books, a

comfortable place in which to peruse them, and a

cheerful librarian with helpful suggestions. Its

invitation is restfully quiet yet audible.

Generally there is a soft shuffling of books.

The canary is apt to sing, or splash, or crack

seeds. The phonograph plays opera on occasion.

The librarian sometimes reads aloud to groups.

And once in a while, a book, too cumbersome for

little hands, falls with a resounding thud.

In this little

library for little folks, I found friends of my

own childhood along with the latest in

children's literature. There were books that

invited song and laughter, books that invited

enjoyment of beauty, books that invited journeys

to real and imaginary places, and books that

invited a better understanding of things close

at hand. There were books that one felt lucky to

discover. There were also some books that made

me wonder why anybody ever bothered to print

them, and some that made me wish they could have

been printed in larger type, or better

illustrated, or put together in more durable

form.

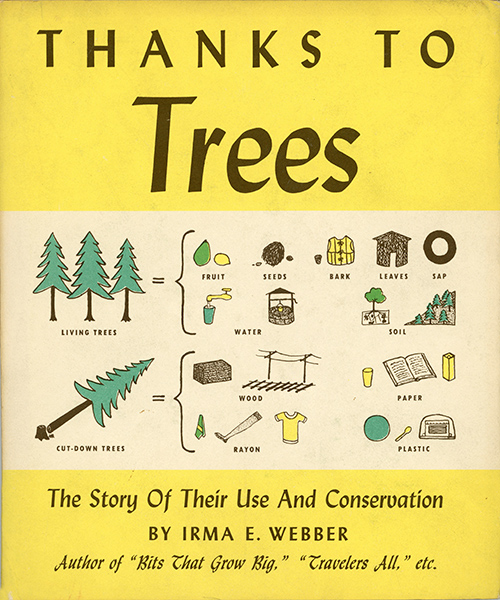

Even with the many

types of books to appeal to many tastes, I found

great gaps in available material that invited

other books for other needs. My own training in

botany, combined with the great pleasure I have

seen many people derive from an interest in

nature, and my own children's early interest in

nature, perhaps made the gaps in factual plant

literature for youngsters seem

disproportionately large·. After bothering me

for some time, these gaps seemed to invite me to

divert some time from technical botany into an

effort to bridge a few gaps in children's plant

literature.

I believe the

response to the little books resulting from this

effort should partially answer the often-asked

question of whether my children's early interest

in nature wasn't an atypical one induced mostly

by heredity, or by association with botanical

parents, a botanical grandfather, and their

botanical friends. Basically the children of

scientists seem to be as human as those of

plumbers or poets. All children normally want

to acquaint themselves with their surroundings,

whatever their environment. Unfortunately, all

children don't have sunny, back-yard playgrounds

where they can become• acquainted with plants

and the animals the plants attract. Yet whatever

their environment, children are little human

beings, and, as such, inescapably concerned with

living things and the forces of nature that

influence all life.

Modern children

often have their early natural desire to learn

about nature's marvels curbed or crushed by

parents or teachers. There are homes where

children are told in very positive terms to

refrain from ever again picking up those

ghastly, disgusting grubs; those horrid, slimy

snails; those awful, wiggly worms; or those

dirty, sticky pine cones. There are homes so

overcrowded, or so full of parents' priceless

bric-a-brac, that they lack any space for a

sparkly rock, a curiously shaped seed pod, or a

beautiful shell that a child finds and yearns to

keep. There are homes where a child's questions

about the sky, the earth, a plant, or any animal

are always answered," Don't know," in a manner

that implies, "And don't care! "

A young child that

has had his desire to learn something about

nature nearly squelched at home, may have the

squelching completed in his early school years.

Where the teacher has a huge class and a

schedule that must be rigidly followed, there is

apt to be little time to look at nature

materials children bring to school, and no time

to answer questions about them. Even where there

is a nature study period, something so rare as a

Southern California hail storm may pass

unnoticed by the teacher because the hail

signals its invitation to look out-of-doors

during the arithmetic period. It takes an

earthquake to awaken an awareness in some

adults of greater things than personal

schedules.

Important as plans

and schedules are, unexpected events often make

changes in them necessary or desirable. How

often the acceptance of a sudden invitation to

the unfamiliar seems doubly pleasurable because

we hadn't scheduled it! Yet the fact that

children's interests so often are aroused

without reference to the schedules of their

parents and teachers too often means that early

interests worth developing are persistently

ignored or repeatedly rebuffed until they

perish.

Fortunate are the

children who learn early that their interests,

regardless of when they are aroused, are always

invited to develop and expand at the library.

Yet even at the library, development of

interests is occasionally curbed by lack of

information in assimilable form. That is why I

feel that inviting, intelligible books about

matters that interest young children are every

bit as important as technical works for

specialists.

|

|

|