|

speech text for City of Los

Angeles Board of Education, Nov. 15, 1944

My

little books, UP ABOVE AND DC·WN BLO'N and

TRAVELERS ALL, are the result of my being both

mother and botanist. While I was trained to be a

teacher, my teachers credential was of the

general secondary kind, and my teaching

experience was at the University of California.

For that reason, my views on science and books

for young children are based mostly on

experiences with my own children and their

friends.

Any mother of young children will tell you it is

a bit difficult to give her family the care it

needs, do the housework, and also pursue a

career. My idea has always been to simplify and

organize household tasks so that they will take

as little time as possible in order to have more

time for other things. As both my husband and

his father are also botanists, they understand

fully why botany should interest me, and have

always encouraged me to devote as much time as

possible to botanical studies.

When my son was a baby, I always reserved his

nap time for my study time. When he reached the

toddler stage and slept less, I often did

botanical work while he played. We had a large

enclosed back yard, and I used to send him

outside to amuse himself as he chose while I did

likewise. In this way I managed to accomplish a

good deal of scientific work despite frequent

interruptions. For Herbert kept coming in with

the request, "Mama, come see"., and I usually

felt that I should see what he had discovered.

Usually the thing that thrilled him was

something that most grownups wouldn't have

noticed, or would have taken thoroughly for

granted. I remember Herbert wanting me to see

clouds move in the sky, plants emerging from the

soil, flowers coming into bloom or falling to

pieces, birds pecking figs, earthworms, rocks,

and insects. And I'll never forget the look of

amazement on hie face when he came in all out of

breath to tell me, "Mama, kitty digs".

Sometimes when Herbert asked me to come see

things, he really wanted me to feel or smell, or

hear something. For he discovered that sunflower

leaves are rough, petunia leaves are sticky, and

rose leaves are prickly, that flowers don't all

smell alike, and birds don't all sound

alike.

When Herbert was four, Irma Jean was born, and

of course that meant , for a while at least, I

would be devoting more time to the family, and

consequently less to botany. In order to give me

a little time for uninterrupted botanical

research, my husband, on days away from the

office, would often take Herbert for a walk

while Irma Jean took a nap. When the walkers

returned I always heard about some of the

wonderful things they had seen. Sometimes it

would be ants, - ants that were red instead of

black, or great big ants that carried seeds even

bigger than they were. Sometimes it would be a

mud puddle, or the way the ground cracked to

form little cakes when the puddle dried up.

Usually, besides stories of interesting things

they had seen, there were pockets, bags, bottles

or cans full of samples. These included rocks

that glistened, rocks that were red or round or

smooth, or that a small boy could break with his

hands. And of course there were seed pods and

autumn leaves and bits of bark, and polliwogs

and pussywillows.

By the time Herbert was ready for first grade he

had a better knowledge of nature and much

greater appreciation of all sorts of natural

history objects than many men. He also had

formed the habit of telling what daddy says

about all sorts of things. This being so, I

probably shouldn't have been surprised when at a

P.T.A. meeting his first grade teacher told me

what was supposed to be a joke. She said that

one day somebody had brought a horned toad to

school, and Herbert, according to custom had

quoted his daddy on the subject of horned toads.

As she wanted to get off the subject of horned

toads and on with the class work that was

supposed to be done that day, she terminated

Herbert's remarks by saying, "That's fine

Herbert. You are a lucky boy to have a daddy

that can tell you about so many things. Some

parents can't do that, because they know only

about their own special kind of work." To that

she said Herbert replied, "Yes, that's right.

Now my daddy knows all about everything, but my

mamma knows just about wood."

Of course it was easy enough for me to see that

Herbert's statement was based on the fact that I

was in the habit of staying home to watch sister

and study the microscopic structure of woods

whenever Herbert and his father went forth to

explore Mt. Rubidoux. And I knew that no normal

six year old could possibly be as interested in

the minute structure of wood as in seeing a

ground squirrel run into its hole, or in

discovering that pine nuts are edible. It was

just a clear cut case of scientific

specialization being much [less] appealing to a

youngster than a general knowledge of nature

which made every day living pleasanter. But I

wasn't content to just realize this, laugh it

off, and let my son continue to regard me as

ignorant, and probably have my daughter grow up

with a similar opinion. It seemed that the best

way I could better Herbert's opinion of me was

to demonstrate that my interest in woods was

only a part of my interest in nature. So the

next time Herbert and daddy went for a walk,

Irma Jean and I went along. As Irma Jean was

only two, she wasn't able to walk very fast or

very far, but we all had a good time seeing

things and talking about them, and inaugurating

our family custom of taking walks together.

With nature walks an established part of our

family life, and a two year old daughter that

didn't like to play alone when brother was at

school, I would have had practically no time for

botanical research if Dr. Gertrude Turner

Huberty hadn't established a small but very good

nursery school for the benefit of her own

children. At this nursery school I knew that

Irma Jean was thoroughly happy and in very good

hands, and while both children were in school I

had a few hours each day for real concentrated

botanical endeavors. But this wonderful set-up

came to an end. The Hubertys moved to Los

Angeles. One of Dr.Huberty's assistants bought

her nursery school equipment, and for a while

ran the nursery school at her home. But before

Irma Jean was four, the school closed. As Irma

Jean craved companionship and was very unhappy

about having to stay at home instead of going to

school, I tried to cheer her up by amusing her

in various ways. She helped me do the housework

and cooking,we worked together in the garden,

played little games, drew pictures, painted, and

of course read books. As plants and animals were

among Irma Jean's major interests at the time, I

tried to get some informational books about

plants and animals that would appeal to her. I

soon discovered that the field of science books

for very young children hadn't received the

attention I thought it should have.

Gradually it dawned on me that it might be a

good plan for me to shift my interest from

intensely technical publications to science

books for young children. It seemed to me that

by so doing, I would be able to spend the time I

liked to spend looking at nature's marvels with

my children without ever questioning that such

time was being spent to beat advantage. Also, I

was convinced that books of the type I had in

mind would be at least as worthwhile a

contribution to society as any of the technical

botanical papers I had written or might write.

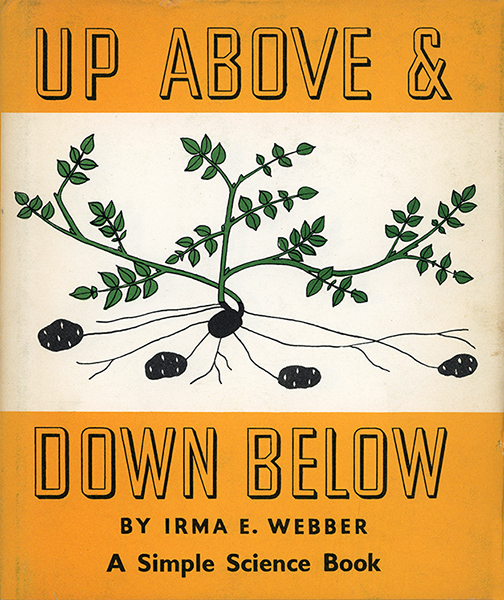

UP ABOVE AND DOWN BELOW was my first book

venture. When it was finished, I got a writer's

magazine listing the interests of various

publishers, picked a place to send the

manuscript, and waited hopefully. After several

weeks it came back, express collect, with

a standard printed rejection slip. In the months

that followed, I acquired what would have been a

discouraging collection of these, if they hadn't

been interspersed with words of praise from

various editors who hoped I would have luck in

placing the manuscript with some other

publisher. Such editors letters made me realize

that publishers are in the publishing business

for profits, that colored picture books are

expensive to produce, that competition in the

field of children's books is keen, and that

books on special subjects do not have as large a

sale as those of a more general nature. Fully

aware of all these things, I sent UP ABOVE AND

DOWN BELOW to William R. Scott Inc.,

Naturally I was thrilled when their editor Mr.

McCullough, wrote that he liked it and wanted to

keep it with the idea of trying to fit it into

their publishing program at some future time.

And I was thrilled again, when Mr. McCullough

wrote that they would publish it if I made

certain changes necessary for more economical

manufacture. These involved changing the book

from one bound at the top to one bound at the

aide, making the story fit into thirty two

pages, and doing over the naturalistic

illustrations so that the book would not require

more than three colors. Mr. McCullough offered

some helpful suggestions as to how to go about

all of these things, and accepted UP ABOVE AND

DOWN BELOW for publication when they were done

to his satisfaction. So, nearly three years

after I had completed the original manuscript,

my first book went on sale. As I had sold all

rights in the book to William R. Scott Inc., it

supposedly wouldn't make any difference to me

how well the book sold. However I was hopeful

that it would sell well, For I felt that it was

really a trial balloon that would indicate the

demand for the sort of books I thought I might

produce. And also, I was hopeful that a

publisher brave enough to accept a manuscript

that had been turned down by so many others,

presumably because it would be unprofitable to

publish, wouldn't lose too heavily on the

venture. Accordingly, I was delighted when Mr.

McCullough wrote that the book selling so much

better than they figured it would, that they

would be able to give me a new contract

stipulating payment of royalties and an option

on my next two manuscripts.

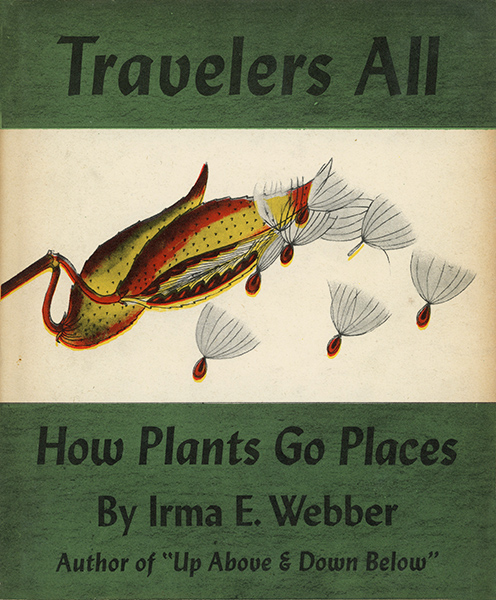

TRAVELERS ALL went directly to William R. Scott

Inc. and Mr. McCullough accepted it. However Mr.

McCullough went into the army before deciding

what changes would have to be made in the

manuscript before it could become a Young Scott

Book. Mr. Scott was responsible for editing this

one, and barely finished the job before he too

went into the army. He felt that tryouts

indicated that children would like it at least

as well as UP ABOVE AND DOWN BELOW, and the

sales record of that book indicated that there

probably would be sufficient demand for

TRAVELERS ALL to permit using four colors in it.

Naturally I am hoping he was right about this,

for it is only as this type of book proves that

it isn't a money loser for the publisher that

others of similar nature will be published. From

my own standpoint, the financial returns for the

time spent are certainly not very great. My

greatest rewards for work of this type are

pleasure in the work itself, and feeling that my

little books are filling a welcome spot in the

lives of children, and perhaps even in the lives

of their teachers and librarians.

|

|

|